CW: Opioid/drug use, overdose

As people wound up their work on a Friday afternoon, Upkar Singh Tatlay tended to emails and phone calls to arrange accommodations for a community member in Metro Vancouver who uses drugs.

“On the community end of things, [we] deal with clients directly, clients being those who are at risk, vulnerable, in-shelters or unsheltered... I have to figure out how to help them,” said Tatlay, Executive Director at Engaged Communities Canada, an organization that provides services such as food security, harm reduction outreach, and youth engagement programs for those facing personal challenges stemming from various socio-economic barriers.

Right before an interview with 5X Press, Tatlay found himself working with various harm reduction techniques for the at-risk community member with multiple addictions—namely heroin and crystal meth—to provide him with culturally relevant support.

“He has a lot of needs; income support, shelter, you name it,” he said candidly, speaking about issues that are usually considered to be taboo topics in the South Asian community.

The stigma and silence around drug use has been deadly for racialized community members, especially in the Fraser Health region, where advocates like Tatlay have worked endlessly to mitigate the lack of culturally appropriate services for substance use and the overdose crisis.

“Does the data match what we’re hearing anecdotally?”

“Every other day, there were back to back days, we were losing a lot of community members all of a sudden,” said Tatlay, referring back to 2016-2017.

A report released by Fraser Health Authority last year, which Tatlay contributed to, showed how South Asians were disproportionately represented in illicit drug toxicity deaths in British Columbia.

Between 2015-2018, these deaths increased by 255% for South Asians as opposed to 138% for other residents in the Fraser Health region.

Additional data showed that 97% of the deceased were men, about half of them were fathers, and two-thirds had partners at the time of their deaths.

“Does the data match what we're hearing anecdotally, qualitatively in terms of narratives? Sure enough, it did,” said Tatlay.

Another staggering finding of the report pointed to how stigma intruded on the network of partners, family, and friends of these men, so many of which lived with mental illnesses and substance use disorders. It added that many of their loved ones did not know or acknowledge their dependence on substances other than alcohol.

Apart from this report, there is no other recent study on race-based data to show overdose disparities in racialized populations, making it difficult to use targeted interventions for specific communities.

“The heartbreaking thing is that we already knew what was going on at the community level. But now we had the data to prove it,” said Tatlay.

Reducing stigma and preventing overdoses through an app

“As a member of this community, those faces [looked] a lot like mine, the people who were dying. They were males, they'd been in Canada, either like myself, born here, or minimum 10 to 15 years. They were middle class-ish. They had jobs, they had families, and they were anywhere between, let's say, early 20s to 45. And they were dying,” he said.

“It’s a heavy thing to weigh on your conscience.”

Tatlay said that he took this data back to his communities to finally have a conversation, which resulted in a fruitful step at destigmatizing the topic.

“They said, ‘we don't know what an overdose looks like. We don't know what toxic drug supply [is]. We don't know how to recognize someone dying of an overdose, or if they’re just in a deep sleep. What is naloxone?’”

An elderly woman asked Tatlay why the solutions were always delivered to the person experiencing the problem, and not those that surrounded their loved ones who needed the support, he explained.

This was a turning point for Tatlay, who went back to Oxus Machine Works (where he is Scientific Research and Development Lead), which led to the birth of an app.

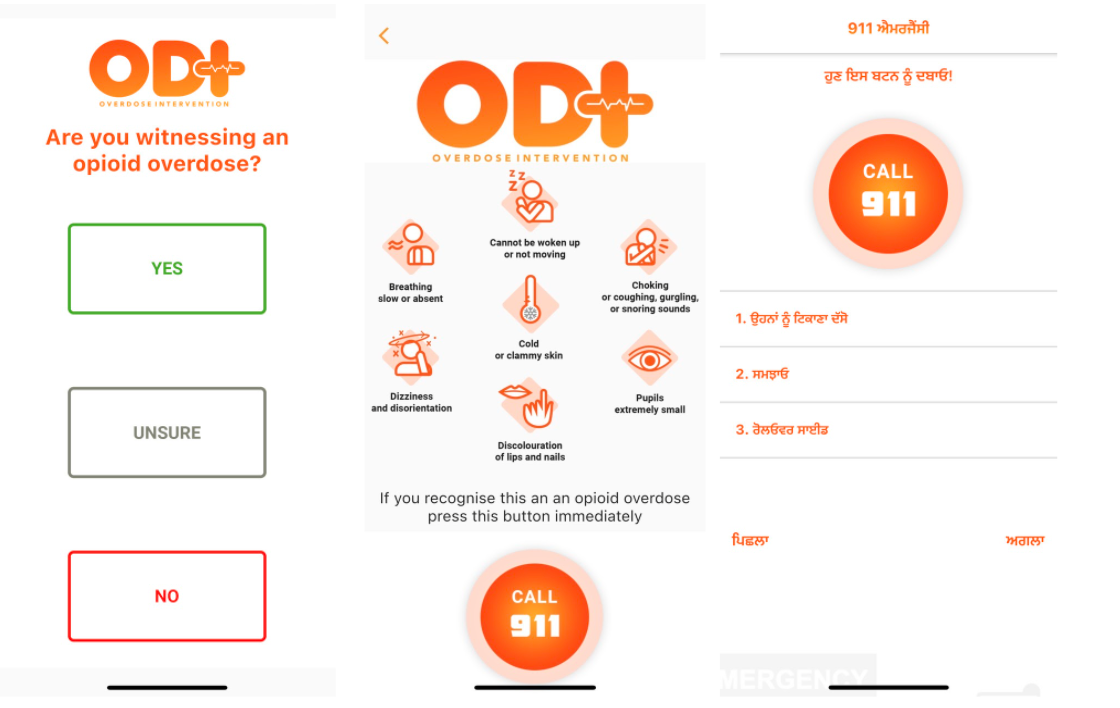

The Overdose Intervention App is a user-friendly app with languages like English, Punjabi, Simplified Chinese, Filipino, and more, guiding people through three different scenarios: when they are sure that someone is overdosing, when they are unsure, and when they want to learn how to resuscitate someone and administer naloxone.

The translations to these languages, which are often not directly available, are custom built and coded by the Oxus team.

In the initial developing stages, the outreach team for the app felt some resistance from the community discussing drug use and overdose according to Tatlay.

“Why don't we take this collective approach, engage everybody in this effort?” he asked.

“From the most senior person in your home to the youngest person and say, ‘look, we have a national crisis, we need all hands on deck, inclusive of every single person.’”

Since then, the stigma has reduced, though there is much more left to do to eradicate it.

“We've had people come up to us and say, ‘I'm able to take this up and ask my grandchild, ‘how do I download this? And as they're downloading it, we go through it together, and it's written in Punjabi, or Hindi.’”

People have pointed out to him how technology has “enabled them to bridge the gap across generations” on something so stigmatizing.

An epidemic lost inside a pandemic

It’s also not news that South Asians have been disproportionately affected by both COVID-19, and the toxic drug crisis.

Previous data has shown how overdose deaths surpassed COVID-19 deaths in the province, exposing the discrepancies in government responses to both public health crises.

However, Tatlay says that he is sympathetic of the fact that COVID-19 response has elicited a faster response from the government, despite harmful comments like those from Premier John Horgan that have misrepresented drug users.

He explains that the pandemic and wildfires have their time periods, and COVID variants call for a stronger response. However, this public health emergency has been unfolding for over 5 years now, making it harder to ignore.

“COVID comes and goes, this Delta variant comes and goes, we’ve got wildfires burning, smog and smoke, and it’s horrible. But the one mainstay, unfortunately, is this toxic drug supply. And it’s killing people.”

What’s next?

Well over 7000 people have died of an overdose since January 2016, averaging at 5 deaths a day, with 2021 being the deadliest year of the crisis.

The province has decided to expand the safer supply program, which will be available through clinics that currently prescribe alternatives to illicit drugs. This has already been criticized as inaccessible, and not enough to provide a low-barrier safe supply.

As overdose deaths are projected to rise, an additional $45 million will be spent over the next three years on supervised safe consumption sites, naloxone kits, and integrated response teams, along with decriminalizing the possession of small amounts of drugs for personal use.

In May 2021, B.C. paramedics responded to an average of 96 overdose calls a day, the highest for a single month in 5 years. Of the 2,977 calls, 803 were in Vancouver and 315 were in Surrey. A grim 160 deaths were reported for the month in total.

Between the two public health crises, recruitment and scheduling of paramedics has been an issue, putting more pressure on the increasing number of overdose calls.

Tatlay, who used to work as a firefighter and a first responder, doesn’t necessarily know how this crisis has affected his own mental health, as he has never had the time to.

Reflecting back on his busy Friday afternoon, he thought about his client who had been using heroin for 15 days.

“I was thinking of the number 15... 15 days of using heroin. What does that do to a human body? He's used meth for five to six years, and now has this whole new sensation of using heroin, and how his body's being ravaged by it. And it's... toxic [drug] supplies,” he said.

In an effort to empower these communities affected by the toxic drug and overdose crisis, he wants the government to realize that a top-down approach can no longer work.

“My hope is that we have the patience and temerity to sit back and listen to the communities that not only experienced [the crisis], but also came up with the solutions for it,” he said.

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

About the author: Karan Saxena (he/they) is a journalist and writer from Mumbai, India. He is currently in Vancouver pursuing his Master of Journalism at UBC. He graduated from the University of Manitoba with a BA (Adv.) in Political Studies and a BA in Women's & Gender Studies. Karan loves researching and writing on queer culture, climate change, immigration, power structures, fascism and violence. He could talk for hours about fashion, French pop music, the ongoing exploitation of the global south, wealth inequality, and the versatility of tote bags!

Subscribe to 5X Press

Join our email list to be the first to receive updates on the latest from 5X Press.